The Treasury has announced that large organisations and those financial organisations which have holdings within them are likely to be required to report the risks which they directly or (via their holdings) indirectly face at the hands of climate change and what they are going to do about it. This will force the organisations so affected to do three things – or risk suffering at the hands of nervous investors: assess the risk to them from climate change; set out how they are planning to adapt to it and what they are doing to reduce their contribution to climate change (both by reducing emissions and where this is not possible by providing offsetting). Here’s the ‘how and why’.

Background

- The April 2009 G20 summit held in London led to the setting up of the Financial Stability Board (“FSB”) under the aegis of the Bank for International Settlements in Basel. In turn, the FSB announced at the UNFCCC COP 21 (04.12.15) the setting up of the ‘Task Force for Climate-related Financial Disclosures’ (“TCFD”). The intention of the TCFD was set out as follows:

“The Task Force will consider the physical, liability and transition risks associated with climate change and what constitutes effective financial disclosures in this area. It will seek to develop a set of recommendations for consistent, comparable, reliable, clear and efficient climate- related disclosures…. The wide range of existing disclosure schemes relating to climate or sustainability highlights the need for companies and relevant stakeholders to reach a consensus on the characteristics of effective disclosures and examples of good practices….”

Effectively it was to become the global hub for a combined approach to corporate reporting of climate change. At that stage it was considered that such disclosures would be voluntary.

- In June 2017 the TCFD (which included amongst its members Chief Executives of such banking giants as Barclays and HSBC) set out its reporting recommendations in respect of larger companies and city fund managers. It was suggested that within each company’s public filings there should be included four areas of information related to climate change, namely

- Governance;

- Strategy;

- Risk Management; and

- Metrics.

It is important to note that the intention was that companies should go beyond mere recording and publication of the level of Greenhouse Gas emissions for which they were responsible. Under this proposal they now had to and to consider the financial implications for that company of the ramifications of climate change. Why is this important? It showed the understanding that mere recording of emissions did not really help either investors to understand how insecure the future of the company was in the light of climate change or to assist that company (or those having holdings in that company) to reduce its carbon footprint.

- A necessary preliminary step in respect of the proposed ‘Risk Management’ reporting requirement within filings was the identification of risk. The suggested list by the TCFD was long and very interesting and included

- the costs of reducing carbon emissions;

- the change in competitiveness arising from having to adopt low carbon technology (this is of particular importance in the aviation industry);

- the costs of adaptation to the physical world changing around them as a result of climate change – changes in storms and flooding patterns on site for example;

- increasing regulatory intervention to ensure compliance with compulsory nett carbon reduction;

- ensuring ‘clean’ chains and finally legal and reputational challenges.

- Balanced against the need to identify risks was the need also to consider the opportunities by changing to a low or nil carbon environment. These included the creation of new markets (one example of which is in meeting the need for carbon offsetting) and, more generally the TCFD considered that

“… services may improve their competitive position and capitalize on shifting consumer and producer preferences. Some examples include consumer goods and services that place greater emphasis on a product’s carbon footprint in its marketing and labelling (e.g., travel, food, beverage and consumer staples, mobility, printing, fashion, and recycling services) and producer goods that place emphasis on reducing emissions (e.g., adoption of energy-efficiency measures along the supply chain)…. and [engagement with] community groups in developed and developing countries as they work to shift to a lower-carbon economy”

In addition it was thought that the adaptation of new technologies might even lead to an overall reduction in costs.

- Perhaps of greatest general importance was the guidance to financial institutions holding positions within individual companies as part of a pension fund, unit trust or direct investment portfolio. The TCFD advised that they should be requested to report on the composition of their funds and how they were engaged. It is worth setting the relevant passage out in its entirety:

“5. GHG Emissions Associated with Investments

In its supplemental guidance for asset owners and asset managers issued on December 14, 2016, the Task Force asked such organizations to provide GHG emissions associated with each fund, product, or investment strategy normalized for every million of the reporting currency invested. As part of the Task Force’s public consultation as well as in discussions with preparers, some asset owners and asset managers expressed concern about reporting on GHG emissions related to their own or their clients’ investments given the current data challenges and existing accounting guidance on how to measure and report GHG emissions associated with investments. In particular, they voiced concerns about the accuracy and completeness of the reported data and limited application of the metric to asset classes beyond public equities. Organizations also highlighted that GHG emissions associated with investments cannot be used as a sole indicator for investment decisions (i.e., additional metrics are needed) and that the metric can fluctuate with share price movements since it uses investors’ proportional share of total equity.

In consideration of the feedback received, the Task Force has replaced the GHG emissions associated with investments metric in the supplemental guidance for asset owners and asset managers with a weighted average carbon intensity metric”

This is a debate which most of us have a stake in. Anyone who owns a pension or who relies upon the profitability of a fund generally needs to know how vulnerable the holdings, upon which returns are based, are to climate change. This, in turn, would place significant pressure on the fund managers both in a direct and an indirect way:

- Directly: they would now have to make it their business to either move their investment to less vulnerable assets or (where they otherwise thought the investment was worth it) persuade those businesses to think more carefully, and act upon, schemes of climate change adaptation, reduction of emissions and/or the acquisition of carbon offset

- Indirectly: since the large financial institutions are themselves large employers with a significant ownership of CO2 emitting assets (tower blocks requiring heating etc), they will have to get their own house in order before they can credibly lecture others.

So what? What’s new?

- In 2019 the UK Government issued its ‘Green Finance Strategy’ and, in it, stated that it expected all listed issuers and large asset owners to be disclosing in line with TCFD by 2022. It then led its own taskforce of government departments and regulators (including the Financial Conduct Authority and the Pensions Regulator) to see how this could be facilitated. In line with the TCFD recommendation, the government is very clear that it too does not just see a leading role for the listed corporate giants (such as Gencorp) but also

“Banks. Insurers, asset owners and asset managers are well placed to identity the risks and opportunities of climate change…both by financing the transition and by addressing systemic financial risks to support a more resilient economy”

(Interim Report of the UK’s Joint Government-Regulator TCFD Taskforce “The Interim Report” 10.11.20).

- The Interim Report is premised on the realisation that the level of voluntary reporting is not good enough (see §1.14). Its primary conclusion is that

“The Government and regulators have concluded that the UK should consider moving towards mandatory TCFD-aligned disclosures across non-financial and financial sectors of the UK economy over the next five years with the most action occurring over the first three years, to help accelerate progress’”

- The intention is that the Government will create a playing field where investors carrying out due diligence can satisfy themselves about any company or fund’s climate emissions and exposure to climate change risk. The warning accompanying this reality is clearly and starkly set out in the Interim Report

“1.12 If information on organisations’ climate-related exposures is incomplete or of poor quality, the future risks to individual financial firms and to financial stability could be considerable”

But again, there is the carrot and stick approach in that opportunities are also referred to within the Interim Report. The annual filings in the new form would

“stimulate the development of green financial products – and competition between providers of these products – with follow on benefits for consumers”

and

“..encourage organisations to behave more strategically, to manage risks better and to ensure they are fit for the future”

- The Government has also set out its intention to include the pension, banking and insurance sector within its overall scheme. Echoing the distinction I drew above between financial institutions qua agents of investment on behalf of others and financial institution qua being its own going concern with its own footprint, the proposal for the financial sector sets the emphasis on the former:

“However, the focus of potential dedicated disclosures for asset managers, life insurers and FCA-regulated pension schemes.. is on information that will be decision useful to clients and end investors.

This is consistent with guidance developed by the TCFD for asset owners and asset managers, which emphasises that the principal source of climate exposure for these organisations is likely to be the assets they manage on behalf of clients and end investors, rather than their own balances sheets”

I maintain, however, the point I made above: the financial institutions will carry much greater authority when placing pressure on their investments if they can point to their own house being clean.

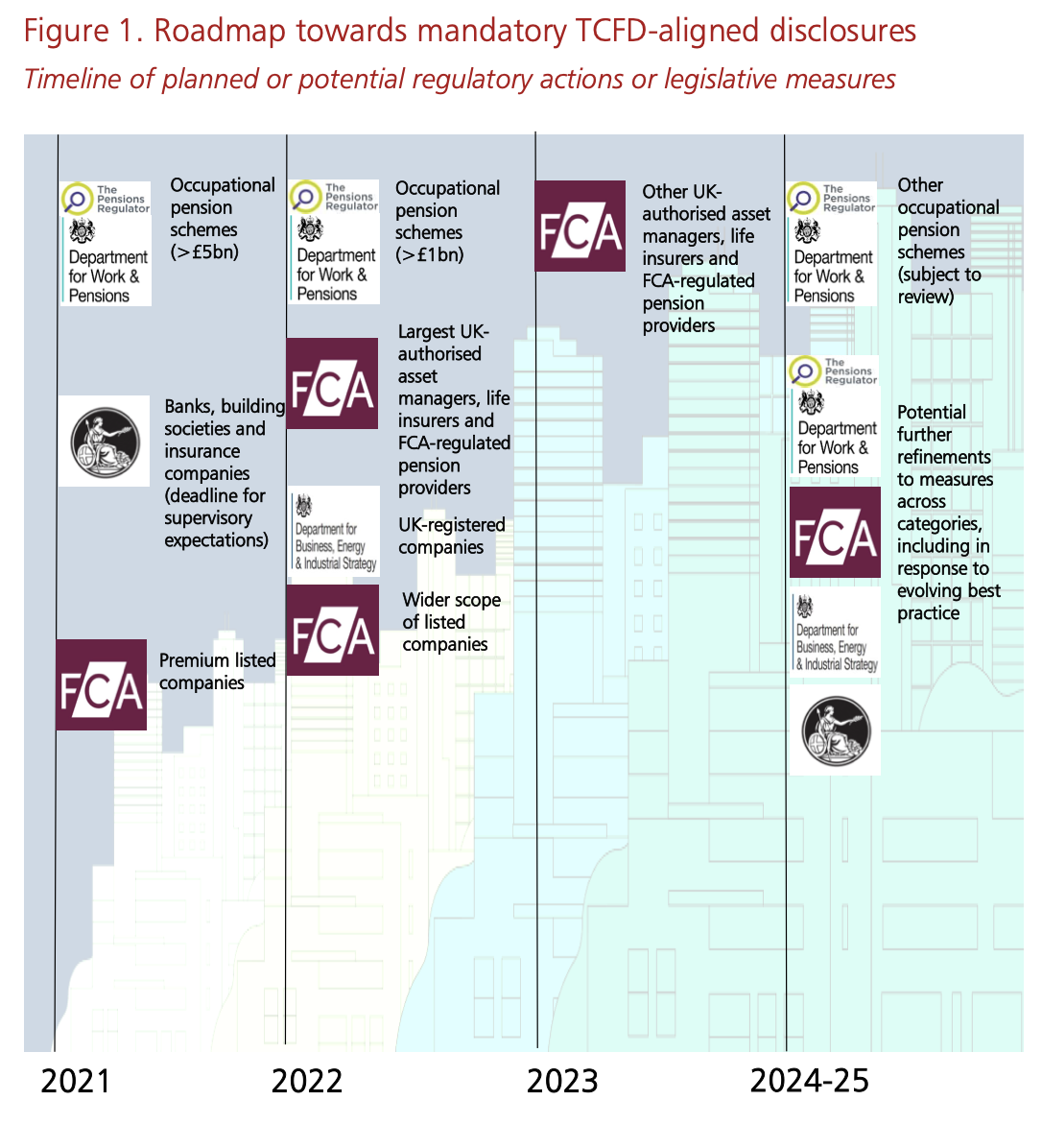

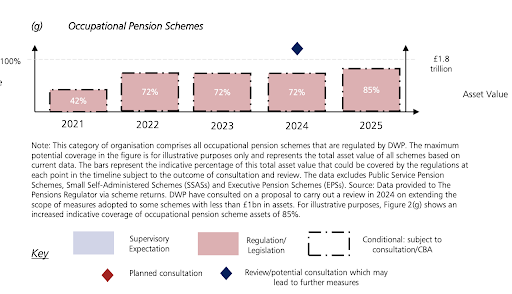

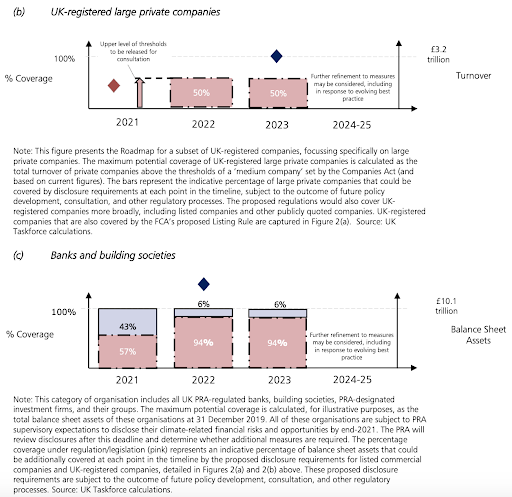

- Although this is a ‘we are minded to enforce but not yet’ conclusion by the Government for the moment, the reality is that since the imperative for change will only get stronger as time passes, it is improbable that anything less than complete voluntary compliance will obviate the need for the imposition of mandatory steps. It is telling that the Government, in setting out a ‘roadmap’ for between now and 2025 (when it expects compliance to have occurred) is ‘front loading’ the requirements as between now and 2023. There will be a formal review for the purpose of the 2022 Green Finance Strategy ‘refresh’ (Interim Report p20) That review will be undertaken in respect of the financial sector by the Prudential Regulation Authority (“PRA”) (Interim Report p14) .

- If the effect of the Interim Report has been sufficient to meet the Government’s intentions, the transition will be completed by 2025 on a formally, voluntary basis. If not, then there will be formal regulation. In either event, it would appear imprudent not to assume that what appears below is anything other than a hard deadline for the larger ie those entities which the report contrasts with ‘smaller, less connected or less complex organisations’ which sector-by-sector may be given more leeway (see p17 of the Interim Report. For the avoidance of doubt, this does not include the financial sector who are already on an accelerated timetable:

“3.13 For instance, in the banking and insurance sectors, climate-related financial disclosures are already reflected in existing PRA policy, in the form of Supervisory Statement 3/19 (SS3/19). The deadline for full embedding of the supervisory expectations outlined in SS3/19 is 31 December 2021. The PRA will perform a review of firms’ published disclosures in 2022, which it will use to inform its decision whether to introduce further measures to improve quantity, quality or consistency”

- The overall transition model and timetable are set out on p13 and pp 14-16 of the Interim Report and are reproduced at the end of this blog. Where does this take us? The Government has effectively signalled a massive expansion of carbon regulation for UK business. So far, only specific activities have been regulated – such as those emitters covered by the EU-ETS or the aviation sector. All other activity has fallen within the voluntary carbon market (both as to reduction and the need for offsetting). However, by this slightly indirect route, the width of quasi-regulation is much broadened. Pending the onset of new technologies, most companies and most funds will need to have a twin track approach of both seeking a reduction in emissions and the offsetting of carbon which cannot otherwise be removed from the manufacturing or operational processes.

MER QC